A case of a large-scale refactoring. 🔗

Let’s say that one day your senior comes and tells you, “Hi Christine, I’ve checked out this new cool library X that solves problem Y, can you try to change some calls as a proof of concept and in the meantime provide us with your feedback on how it affects us?”

So you become excited, you get the opportunity to dirt your hands with this new hotness that everyone in the community speaks about, and prove yourself to the team. AWESOME!

As you go about the documentation, you get the feeling that this library is really a lifesaver, and should indeed be integrated with the rest of the codebase. On the downside, there is big gotcha. Migrating from the current implementation to the new is not going to be easy. Your only choice is to create a new branch with the new feature, and merge it back to the trunk(a.k.a. master). Or is it not? You don’t want to be the one to make that huge pull request. You only need to implement that small set of simple calls to the new library and leave the rest be. How do you do it?

Enter Branch by Abstraction. 🔗

Bearing in mind that you do not want to be in a situation of a huge merge, and that the changes need to be published to the rest of the team as soon as possible, with some research you can stumble upon a technique named “Branch by abstraction”(BbA for the rest of the post). Originally it was introduced by Paul Hammant and described by Jez Humble as well.

But what exactly is BbA and how does it differ from the classic feature branching in version control?

Quoted directly from Martin Fowler :

“Branch by Abstraction” is a technique for making a large-scale change to a software system in gradual way that allows you to release the system regularly while the change is still in-progress.

The name of the technique is a little bit misleading, as it contains the term “branch” in its definition, which almost immediately hints that we’re speaking about branching as in creating a new branch in source control. On the contrary, the technique is advocated by trunk based development , a source control branching model where all developers push directly in the mainline. Rather than branching in source control, the “branching” happens in the code directly.

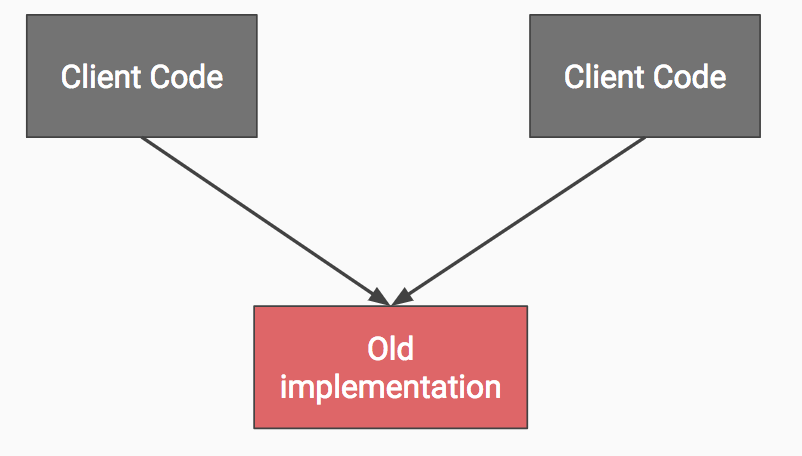

Let’s say the initial structure of your code is something like this:

Initial Structure.

The steps for BbA are:

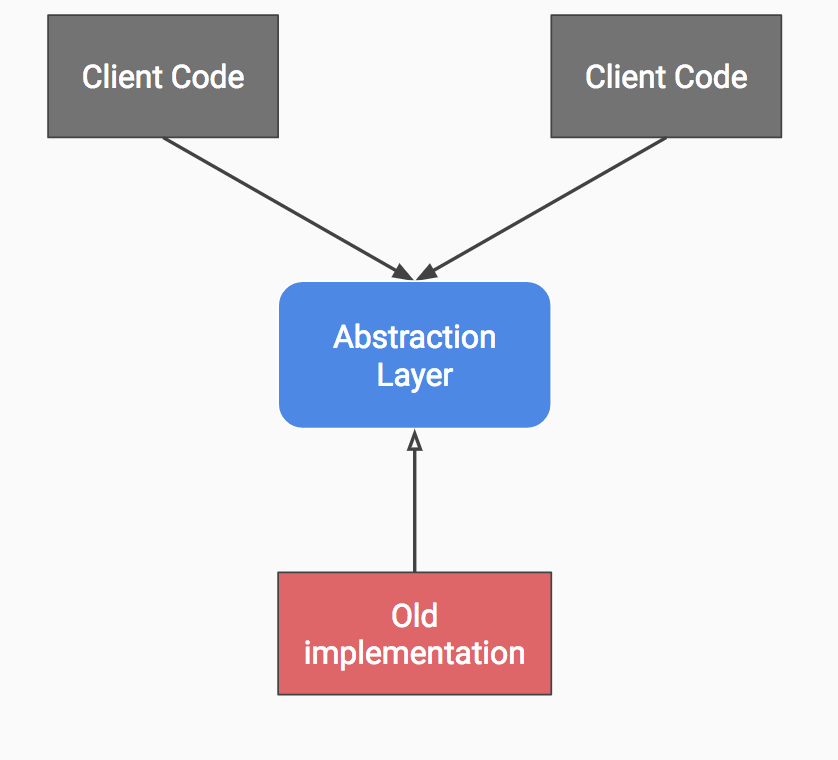

- Add an abstraction over the current old implementation.

- Refactor so all the clients use the abstraction above instead of the old implementation directly.

Steps 1 & 2.

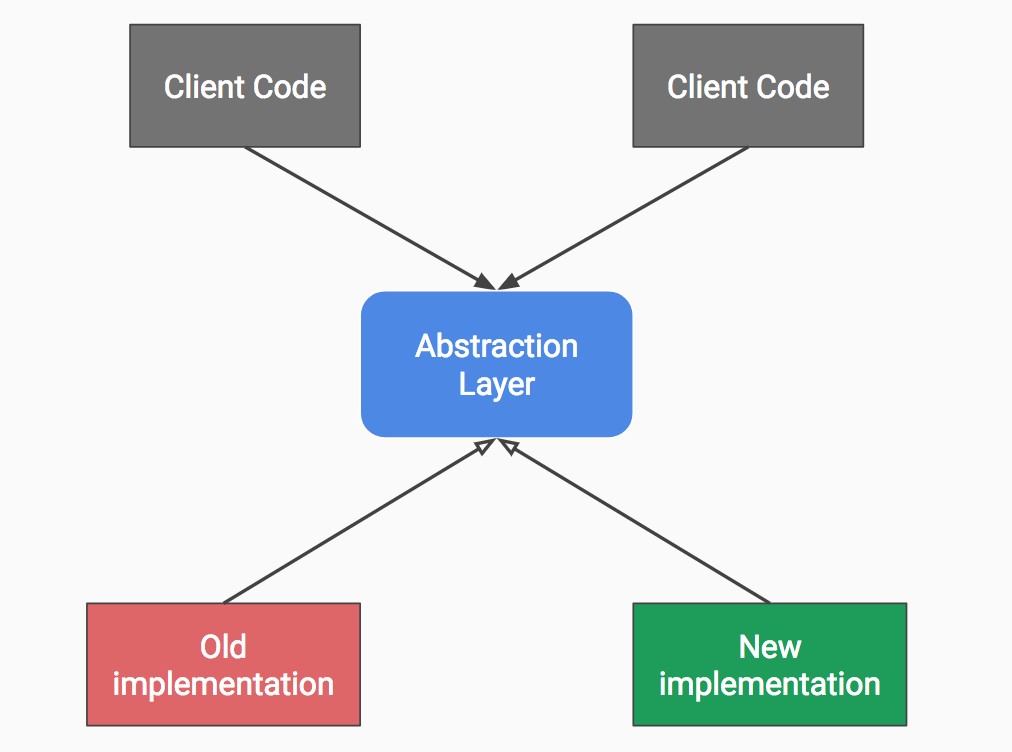

- Add the new implementation under that abstraction and gradually delegate to the new implementation as needed.

Step 3.

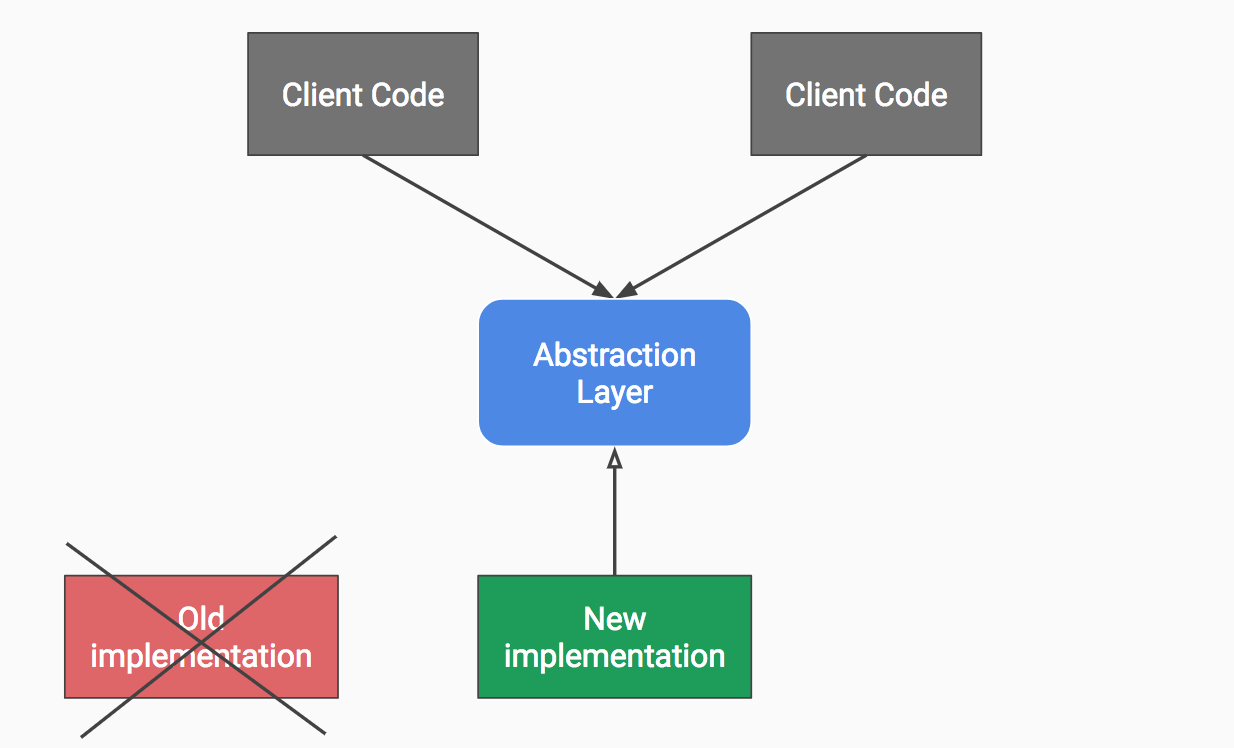

- Once the old implementation is no longer used, it can be deleted.

Step 4.

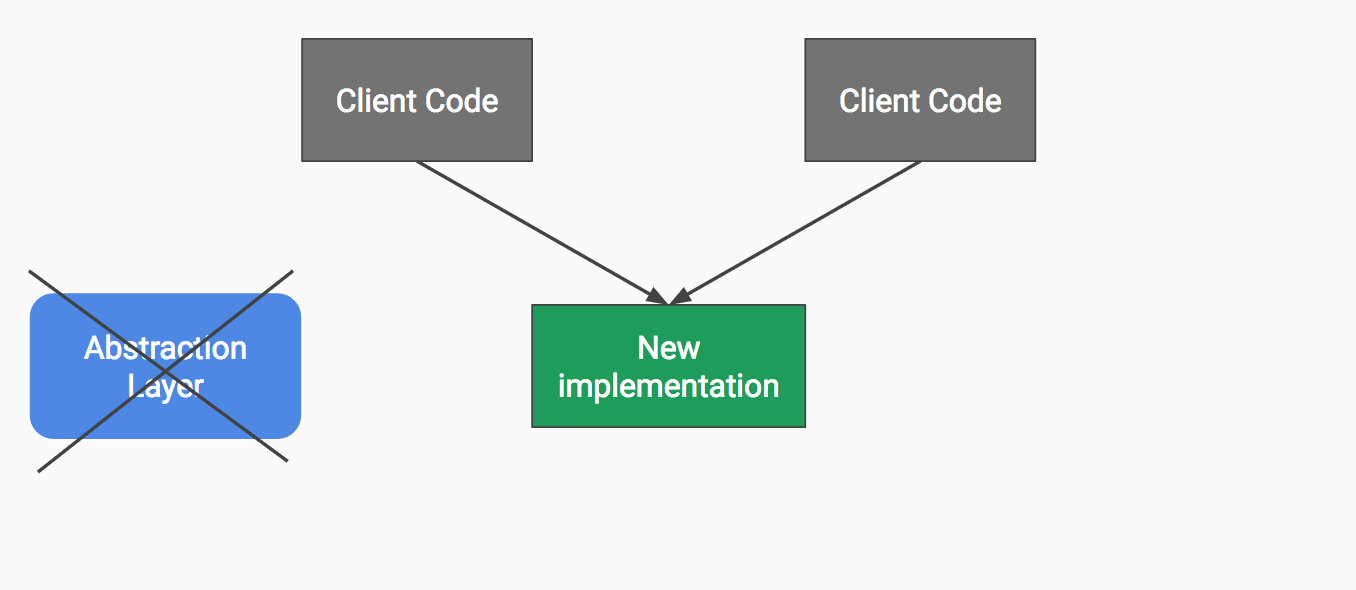

- Once the refactoring is over, delete the abstraction layer.

Step 5.

Although Martin Fowler describes some variations, the general idea is that you create an abstraction over the implementation that needs replacement, find the appropriate behaviour that the abstraction must implement, change the client code to use that abstraction and incrementally add the new code.

What’s more you can use feature toggles , so you continue to deliver software, even if the the new implementation is unfinished.

Pros and Cons 🔗

Every technique has its ups and downs, and BbA is no short of its own:

Pros:

- No merge hell.

- It is possible to extract behaviour that the old implementation should’t have, thus making the system more cohesive.

- Code is continuously integrated, thus always on a working state.

- You can deliver anytime, even with the feature unfinished.

Cons:

- Development process may slow down, as it is not always easy to introduce the required abstraction, or to make the two implementations co-exist during the refactoring.

- Difficult to apply if the code needs external audit.

Show me the code 🔗

Of course, talk is cheap and a simple but non trivial example is worth a thousand words. Let’s create a simple app which saves quotes and then lists them(named with an extra dose of imagination “QuotesApp”).

For QuotesApp we will use a MVP pattern. The Presenters will hold a QuotesRepository directly instead of UseCases and the QuotesRepository will have a QuotesDataSource for storing the quotes locally. In the role of our legacy library we will use SqlBrite2 and we will try to replace it gradually with the new Room library. The full code of the example is here .

public interface QuotesDataSource {

Observable<List<Quote>> getSavedQuotes();

Observable<Boolean> add(Quote quote);

}

public class SqlBriteQuotesDataSource implements QuotesDataSource {

private final BriteDatabase briteDatabase;

public SqlBriteQuotesDataSource(BriteDatabase briteDatabase) {

this.briteDatabase = briteDatabase;

}

@Override

public Observable<List<Quote>> getSavedQuotes() {

// get quotes with SqlBrite

}

@Override

public Observable<Boolean> add(Quote quote) {

// save a quote with SqlBrite

}

}

We will use the QuotesDataSource interface to introduce the abstraction needed for our BbA powered refactoring. In Java this would look something like below. We would make the abstraction implement the QuotesDataSource and then manually delegate all method calls to the old implementation. Then in our dependency injector we would wrap the Sqlite implementation with the new mixed data source.

public class MixedSqliBriteRoomDataSource implements QuotesDataSource {

private final QuotesDataSource oldDataSource;

public MixedSqliBriteRoomDataSource(QuotesDataSource oldDataSource) {

this.oldDataSource = oldDataSource;

}

@Override

public Observable<List<Quote>> getSavedQuotes() {

return oldDataSource.getSavedQuotes();

}

@Override

public Observable<Boolean> add(Quote quote) {

return oldDataSource.add(quote);

}

}

Excuse me, where is my Kotlin twist? 🔗

In this example we only have two methods, but one can imagine a huge api with a hundred or more methods. Wouldn’t it be tedious and error prone to manually delegate to the old implementation? So far, Kotlin has not shown up in the post, and now is the time to make its magical appearance. We could use the power of Kotlin’s built in delegation and make the abstraction delegate by default to the old implementation:

class MixedSqliteRoomDataSource(private val oldDataSource: QuotesDataSource)

: QuotesDataSource by oldDataSource

This is not only terse and concise, but also saves you from the errors that anyone can easily do during manual delegation.

Back to Refactoring 🔗

Continuing with the refactoring, we would introduce the new implementation, and pass it as a second argument to our abstraction. Then finally, we would override only some of the methods in our abstraction to delegate to the new implementation.

class MixedSqliteRoomDataSource(private val oldDataSource: QuotesDataSource,

private val newDataSource: QuotesDataSource)

: QuotesDataSource by oldDataSource {

override fun getSavedQuotes(): Observable<MutableList<Quote>> {

return newDataSource.savedQuotes

}

}

This is much easier to push directly to the mainline, or if you’re in favour of code reviews, make a short lived version control branch and open a pull request from there.

As you add more and more methods in your new implementation, the old one and the abstraction will become obsolete, and finally you will be able to delete them.

Final Thoughts 🔗

So far, BbA seems to be quite a sane way for making large-scale changes in your codebase. It may not be always easy to make the old and new implementations coexist, but all in all, it seems to be worth the effort. What’s more, we can use the power of Kotlin’s delegation to quickly implement only a set of behaviours in order to provide a proof of concept, and then continue with the rest of the refactoring.